by Kristin Rasmussen

Once again, our Panama whales continue to surprise us by turning up in far-flung locations. This time, one of our whales was sighted on the other side of the Pacific, off New Caledonia! This is the greatest distance over which a whale sighted in Panama has ever been resighted.

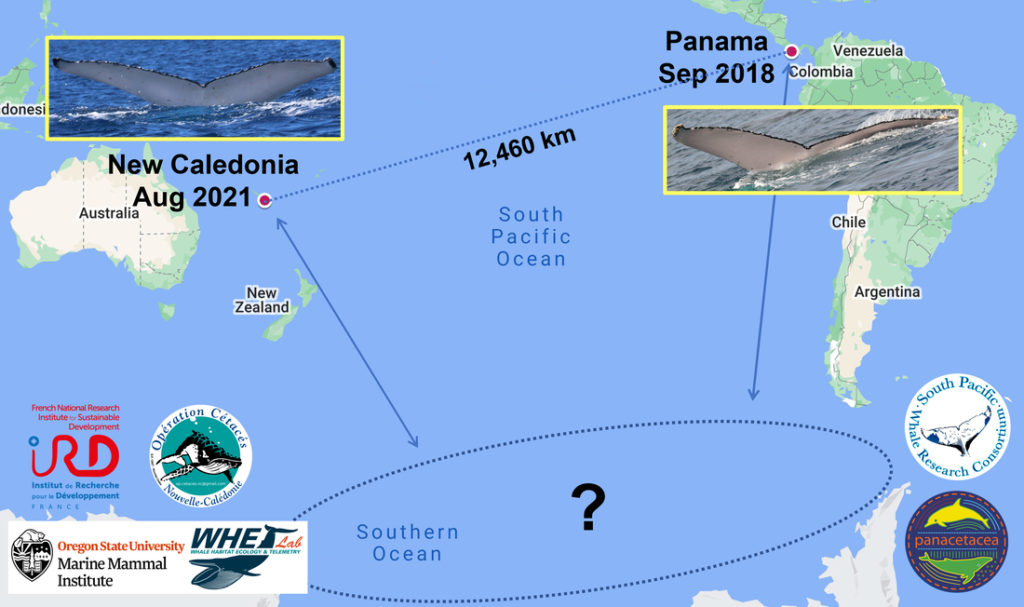

This migratory record was discovered by the Cetacean Conservation and Genomics Laboratory (CCGL) in collaboration with the Whale Habitat Ecology and Telemetry Lab at Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute. We shared 197 genetic samples from whales sighted off Panama between 2017-2019 with the CCGL, which they compared with their collection of over 5,000 DNA profiles from humpback whales in the Southern Hemisphere. A genetic match was found for one of our whales seen off Panama in September 2018. This whale matched an animal sampled off New Caledonia in August 2021 by our colleague Dr. Claire Garrigue from IRD (French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development) and Opération Cétacés. Fortunately, this whale was photographed both in Panama and in New Caledonia when the genetic sample was taken, and a comparison of the fluke ID photographs confirmed the genetic match. CCGL’s genetic analysis also revealed that this whale was a male. When the whale was sighted off Panama it was in a large competitive group (a group of males competing to mate with a female). It was alone when it was sighted off New Caledonia, and for both locations, it was the only time it was seen. The great circle distance (which takes into account the curvature of the earth) between the two sightings was approximately 12,640 km.

As we have discussed in a previous blog post, we are seeing an increase of our Panama whales sighted in areas outside of where we typically see them. As the population increases in size, whales are likely expanding their range, or reinhabiting previously populated areas. It’s also possible that they are seeking new feeding areas as pressures like climate change affect their prey resources. Whales that breed off Panama (referred to as “Breeding Stock G” by the International Whaling Commission) are typically seen feeding off the Antarctic Peninsula or southern Chile, but they have also been sighted in feeding areas off the South Orkney Islands (east of the Antarctic Peninsula) and the Amundsen Sea (west of Antarctic Peninsula), as well as in the Kermadec Islands, a migratory corridor between feeding and breeding areas for whales breeding in Oceania. As these whales wander into other feeding areas, they would likely encounter whales from other breeding areas, and it’s possible that they would then join these whales on their winter migration back to a different breeding area.

This particular whale had a lot of white pigmentation on its sides, which is not something we usually see off Panama, but a trait more commonly seen in whales around Australia and Oceania. Perhaps this was not a “Panama whale” visiting New Caledonia, but it was a whale originally from New Caledonia that was visiting Panama! Previous studies have shown some genetic similarities in Stock G whales and breeding stocks in Oceania, specifically with Breeding Stocks E2 (New Caledonia), E1 (Tonga) and F (French Polynesia), so we know there has been some mixing between these populations in the past. Further analysis of the genetics should give us clues as to where this whale was originally from.

Understanding the movements of humpback whales and how the different populations relate to each other helps us to better understand what measures need to be taken to ensure that these populations can continue to grow and thrive. The genetic and photo-identification data are fantastic tools that are continually revealing new information about these whales.